What is the first image that comes into your mind when you think of your father? First words, feelings, memories? Do you like him? Do you converse with him? What topics do you discuss? Has the way you relate to each other changed in recent years?

These were the initial questions that shaped the Father project. One day, we were sitting around discussing the need to create a film that would express our experiences during the period of transition that followed the fall of communism. We wanted it to be a unique reflection of our collective struggle for identity, spoken in a familiar language that we could all directly relate to. The figure of the father appeared to be a wonderful metaphor that encompassed this idea. First and foremost, we all have our own unique relationships with our fathers, but beyond this, the father is the first to provide us with sensations of power, authority, and responsibility. What happens to us as individuals, and to our families, when the models of authority and responsibility in a country change, as was the case after 1989? What happens to the child and the father? These were the intriguing questions we decided to explore further.

The initial conversations between us, the creators of the project, took place in our kitchens, at home. Ivan, Maria, Vessela and I, recorded our discussions over the course of a few days. These were the first databases that we compiled. We noticed an overall intrigue and enthusiasm in all of the participants, which in turn led to the creation of new and unexpected channels of thought. Afterwards, I continued the discussion outside of our homes, meeting various acquaintances who willingly and openly shared their stories. All of these people are part of the generation that had experienced the period of transition at a conscious young age – between 13 and 20 years old.

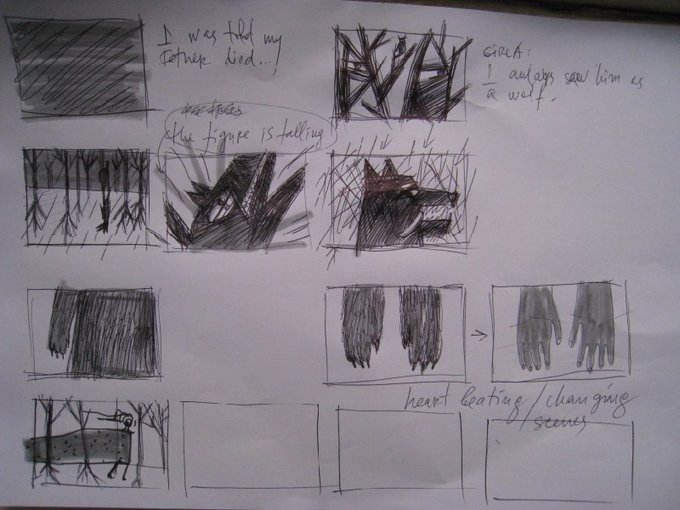

We collected nearly fifteen interviews, and even though my interest was growing we had to draw it to a close, after all, this was an animated documentary project and the database was only its foundation. We focused on seven of the stories, selecting the narratives that we found the most interesting and diverse. We then gave five directors the opportunity to choose the story that they would most like to work on.

Some interesting facts surfaced during the process. I was personally surprised to find so much pain and sadness in the stories about the fathers. In most of the stories the figure of the father was missing either physically (emigrated, deceased, left the family, etc.) or mentally (lack of support and a feeling of presence). I will never forget one of the most moving conversations I have ever had. I was listening to the story of a girl and suddenly exclaimed, “You have actually never addressed anyone with the word dad?” She went silent for a moment and responded “Never, never to anyone”.

Father is a subjective personal project. It came to life because a small group of people were moved by the concept and decided to make it a reality. Perhaps, when one is watching this film, there is no need to think about the communism, the period of transition, and everything connected to it. These stories transcend Bulgaria, they could take place in other geographical locations and periods of transition. Furthermore, it is precisely these types of considerations that give meaning to our personal experiences.

This journey signifies the very essence of Father. The film begins:

“What is the first image, that comes to your mind when you think of your father?”, “Do you like him?”, “Do you converse with him?"

This question provides the emotional framework of the film, and it is this idea that drove us to explore this issue initially, not in search of definite answers, but to provoke a deeper discussion on a topic which so many of us have a poignant personal experience and connection to.

Watch here the first impressions from the directors at the very beginning of production...

Extracts from the interviews:

BORIS:

“My father wanted to make me a kite. It was an octagonal kite and it had a long orange and white tail. But we couldn’t get it to fly. My father finished it, a really beautiful kite, he even decorated it with black pictures from ‘Nu, Pogodi!’*, cut out from somewhere, and it was so beautiful. I think both of us were very disappointed that it didn’t fly. We had put so much effort.”

*Nu Pogodi! (''I'll Get You!') is the most popular cartoon of the Solviet Union, created from 1969.

SANCHO:

“The first that comes to mind – I was with my mum at my grandma’s, he was in the army but suddenly appeared at the door. He always wore a beard, he was a long-time hippie, and I opened the door and there was a familiar face; I must have been 4 or 5 at the time; a familiar face but no beard and no moustache, short hair, which was so unusual for him. I got really scared, ran away and hid under the bed. So this is my first memory.”

YANA:

“He was and I will always remember him as a playboy. He was very handsome, especially in his youth – tall, with black hair. He always drove expensive cars. He would often wear a light-colored suit, which was rare at the time. He looked very elegant in a suit – there are men who don’t look good in a suit, but he was not one of them. I would watch him put on his tie in the morning – he was very good at it. He was so elegant!”

SIRMA:

“My first memory of my father… a big unknown. I actually don’t have any memories of my father. What I remember is how I felt about him, the questions, trying to find out about him. I first looked, of course, in the family albums, I searched through all drawers and cupboards. I knew the official story, I’d heard it from my mother, she tried to convince me it was true. Such were the times, every child must have some story about their father. And she had given me mine. So I was told my father had died, he didn’t exist.”

VELINA:

“I have this memory which never fails to amaze me. I am at home – I must have been 5 or 6, it was in the late afternoon, around seven o’clock. So I am sitting on the arm of a chair, swinging my legs, observing my mother and father running about, getting ready to go out. And suddenly I saw them as two monsters. I saw them without their skin. It was very strange, but didn’t scare me at all... I was just sitting there thinking – how strange.”